El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO is a fluctuation of ocean temperatures and atmospheric pressure in the Pacific. It is made up of opposite phases - El Niño and La Niña - and has a considerable impact on global weather, including here in New Zealand.

Earth Sciences NZ meteorologist Chris Brandolino says as our climate and seas warm, they’re interfering with the long-standing method used to monitor the ocean component of ENSO.

“Traditionally, ENSO is tracked by measuring how unusually warm or cool sea surface temperatures are in certain areas of the Pacific. However, as the climate warms, so do our oceans, which can muddy the ENSO waters. As ocean temperatures increase, we can overstate the frequency of the warm phase of ENSO, or El Niño, and understate the cool La Niña phase,” said Chris.

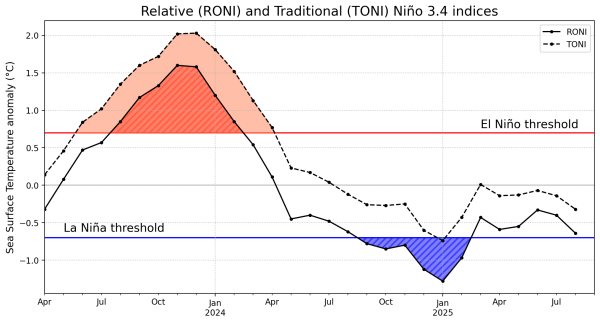

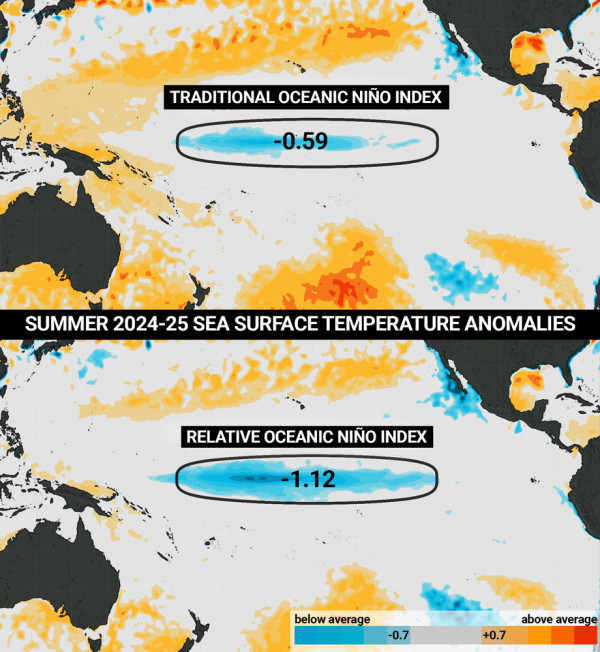

For example, during summer 2024–25, the traditional Niño index (TONI) did not reach the threshold of –0.7°C to classify La Niña. However, La Niña-like conditions were still observed across New Zealand, with above average air temperatures, widespread marine heatwave conditions, and rainfall totals that were above normal in eastern areas and below normal in western areas.

A graph showing the sea temperature thresholds of the traditional method vs the new relative method for defining El Niño and La Niña.

“In response, we’re updating the way we calculate the sea surface temperatures anomalies, or difference from average, that help us track and forecast ENSO” says Chris.

The move follows a similar announcement by the Australian Bureau of Meteorology last month.

The new approach uses a method that assesses how unusually warm or cool ocean temperatures are in specific locations compared to the current tropical mean temperature (averaged between 20° south and 20° north).

“Had this been applied during summer 2024-25, the La Niña classification threshold would have been met, demonstrating how the updated methodology better reflects ENSO impacts in a warming climate,” says Chris.

A graphic showing the sea temperature thresholds of the traditional method vs the new relative method for defining El Niño and La Niña.

While ENSO remains a key driver of climate variability in New Zealand, it is only one part of a complex system.

For the most reliable guidance on expected rainfall and temperature patterns in the coming season, refer to our Seasonal Climate Outlook.